Negotiation Lessons from United Airline’s Bonus Lottery Plan

By Chuck Doran and Megan Winkeler

It took United Airlines three days to “press the pause button” on their new core4 Score Rewards program. The program replaced employees’ quarterly performance bonuses with a chances to win prizes quarterly including, “cash ranging from $2,000 to $40,000, luxury cars, vacation packages, and a grand of prize of $100,000 awarded to one eligible employee per quarter.” There was immediate backlash from employees who disliked the lottery system, with reactions published on the company’s online employee board, a Change.org petition, and Twitter. Incensed employees lamented losing up to $1,500 per year in bonuses so that a lucky few could reap sizable benefits; one person said that it “made us feel precisely like Clark Griswald felt when awarded the jelly-of-the-month club membership” in reference to National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation.

They made the announcement through a memo on Friday. By Monday, the airline’s President Scott Kirby put the program on pause. What went wrong? Reviewing the roll-out of the core4 Score Rewards program from a negotiation perspective, there is a lot to learn.

- Carefully craft and time your message: When overhauling such an expansive and important program for employees, it’s important to think about the timing of you announcement. Unfortunately, United employees were already unhappy about bonuses before the core4 Score Rewards program was announced. “Industry friends” at airlines like Southwest and Jet Blue received $1000 tax-cut bonuses this year, but United chose not to provide similar bonuses to their employees. Building on this, United is also currently negotiating a new union contract with pilots, and the union was very displeased to learn about the proposed lottery system replacing bonuses. A spokesman for the pilots union said that “this just puts a bad taste in our mouths.” Moreover, the program was announced via memo on a Friday. For worried and disgruntled employees, this system left no room to ask questions and discuss their concerns. It also gave people a weekend to ruminate as corporate offices closed and front-line employees continued working.

United could have improved the reception of their announcement had they thought more about when and how they made the announcement. Overhauling a program that provides employees with a significant amount of money each year would inevitably upset people. Had they provided more information about their reasons for changing the bonus structure, recognized that employees may have questions and concerns, and made space for employees to share those concerns privately, debate about the program could have been managed internally. And announcing the program as a Friday afternoon news dump does not inspire respect and confidence from employees. It may allow you to bury the story in the news, but your employees won’t be as quick to forget. - Consider both side’s interests: United saw significant improvements in their performance in 2017, setting all-time records in almost every metric and leading the industry in for departure time performance. Given that the airline’s performance was strong with the performance-based bonus structure, what interests did the new rewards program meet for United? Perhaps they were seeking ways to save money. The core4 Score Rewards program also required perfect attendance to be eligible, so they may have also been interested in improving employee attendance through the bonus structure as well. However, United’s President Scott Kirby also stated that he wanted to build an image of United as a “caring” airline, and the new bonus program failed to meet that interest.

To show they cared – and to create a program employees were more likely to appreciate -, United should have explored employees’ interests in depth. Had they done so, they would have realized that the possible $1,500 in bonuses represented a significant portion of many employees’ salaries. They would have recognized that employees already had qualms about their ability to use sick time; since the core4 Score Rewards program required perfect attendance to win, anyone who took a day off would be ineligible. As one employee shared in an online petition to end the new program: “When no one ‘qualifies’ because they called out sick due to the most awful flu in years, or sick children, or life … the company just makes more money for itself.” Had United considered employees’ interests alongside their own, they would have seen that the new program met few of either side’s goals and needs.

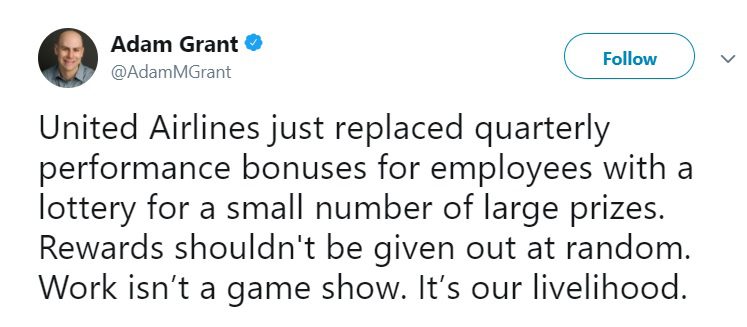

- Think about the perception of fairness: In last week’s blog post about objective standards, we introduced the Test of Reciprocity. If you are offering a deal to someone, ask yourself if you would accept it if someone offered you the same deal. If your answer is no, then the offer is probably unfair or fails to meet important interests. This employee’s tweet sums up how the new bonus program failed the Test of Reciprocity:

United also could have looked to industry standards around employee bonus structures, or they could have consulted with airline or workplace experts. Doing so would allow them to justify their decision with objective standards. Of course, they also could have utilized objective standards to reevaluate their options prior to announcing the program. One workplace expert stated that “I really thought [the bonus program] was a joke when I first heard of it.” That kind of feedback from an expert would have been helpful during the brainstorming phase, not in an article documenting the fallout from the decision.

United also could have looked to industry standards around employee bonus structures, or they could have consulted with airline or workplace experts. Doing so would allow them to justify their decision with objective standards. Of course, they also could have utilized objective standards to reevaluate their options prior to announcing the program. One workplace expert stated that “I really thought [the bonus program] was a joke when I first heard of it.” That kind of feedback from an expert would have been helpful during the brainstorming phase, not in an article documenting the fallout from the decision.

- Ask for input: Imagine that United announced the core4 Score Rewards program not as a replacement but as a possibility. Imagine that they asked employees to share their thoughts and feedback directly with leadership so they could evaluate how well the program met their needs. Or imagine that they held focus groups with select employees to gauge their reactions in a private forum before other employees heard about the possible changes to the bonus structure. One writer who reviewed comments on a United Airlines employees-only forum noted that “of roughly 500 comments I read, four were positive (and three of those were from the company’s vice president for human resources, responding to the negative comments).” Imagine if United had garnered those responses prior to announcing the decision. They could have avoided a PR disaster.

It can be easy to overlook the importance of asking for the other side’s input in a negotiation or as an executive running a company, but the benefits are extremely valuable. You learn more about the other side’s interests. You learn where they see unfairness that you might not have anticipated. You are exposed to ways of viewing the issue that are only apparent to someone working in a different role. When it is time to make a decision, you want to do so decisively and stick with your decision; this can scare some people from asking for input prior to make a decision, but they shouldn’t be concerned. Had United asked for employees’ input prior to announcing their decision, they could have preempted universal, passionate, and public backlash.

Although United made several errors rolling out the core4 Score Rewards program, their prompt response to employees’ concerns showed that the company listened to and cared about the feedback. Rather than sticking with a bad idea out of pride or embarrassment, President Kirby’s swift response on Monday moving to “pause” the program may have helped rebuild some trust. If they can learn from the mistakes made during the roll out of this program, they can improve and create an even better program in the process.

All negotiators take action that, in retrospect and from afar, was clearly a mistake. However, the mark a strong negotiator is one’s ability to review and learn from those mistakes. Figuring out how to bounce back and reset the stage is a skill in and of itself, and it’s something that we can all learn from.

If you enjoyed this article, consider checking out MWI’s blog post suggesting books to build on your negotiation skills. Want to build upon the negotiation skills you’ve read about? Contact Chuck Doran at 617-895-4026 or cdoran@mwi.org to learn more about how MWI can help you become a better negotiator.